In 1971 three students at Carleton College in Northfield, Minnesota came up with the idea to do something new with computers. Don Rawitsch, Paul Dillenberger, and Bill Heinemann were studying education and about to start work as student teachers. Rawitsch was tasked with 8th grade American history and wanted to make something more interesting and engaging than the usual lecture or boring reading. He wanted to engage the students in new and exciting ways, so Rawitsch began to prototype a tabletop game that simulated being a pioneer. It was originally played with dice, but Dillenberger and Heinemann suggested a different method. Both had received rudimentary training in computer programming, and in Rawitsch’s game they saw something that could translate well to a computer. Though none of them was an expert at code, Rawitsch described that they did have “an understanding of how an event could be simulated mathematically by setting up algebraic relationships between variables that represented the impact of user decisions, the financial value of supplies, and random events.” In two weeks, the trio was able to create a working version of a game they called “the Oregon Trail.”

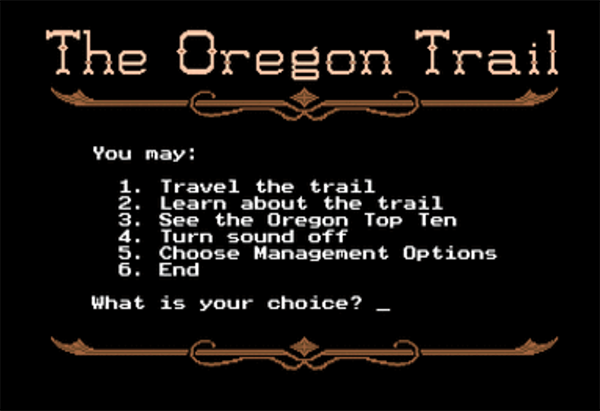

Rawitsch, Dillenberger, and Heinemann’s game placed players in the role of a wagon leader journeying on the Oregon Trail from Independence, Missouri to Willamette Valley, Oregon in 1848. At the beginning of the game players make crucial decisions on how to spend a limited set of funds on supplies such as bullets, clothing, food, and oxen. Players faced further decisions on the trail, most of which were generated at random by the computer. As Rawitsch described: “We designed the game so there would be many different options from game to game. Each turn, you might proceed forward. You might stop at a fort. You might go quickly. You might go slowly. You might eat a lot. You might eat a little. Each of those decisions had implications for your resources and how quickly you made your way across the trail.” (Wong, 2017).

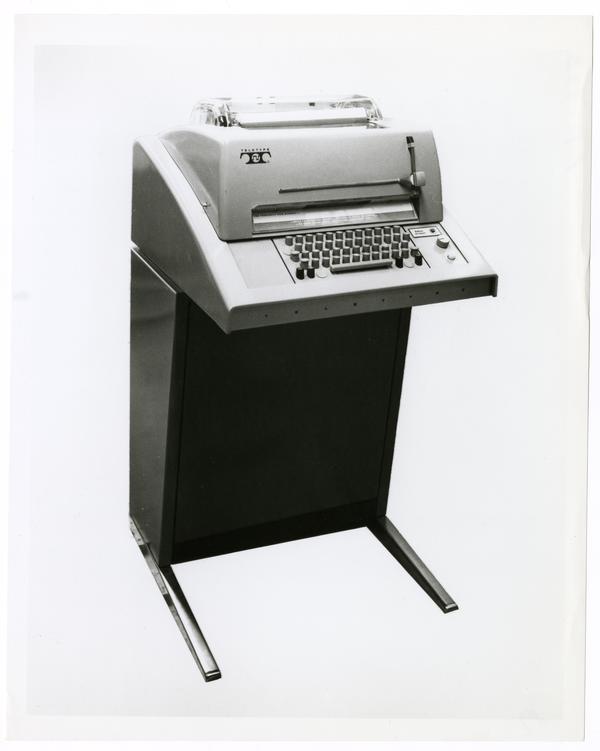

The Oregon Trail was a remarkable achievement in game design. The first version was text-based and ran using a teletype: an typewriting console that communicated with a mainframe computer via phone lines. Players typed in numbers to choose from various presented options such as “run” or “attack.” To successfully hunt for food, they had to type a randomly selected gunshot sound like “bang,” “pow,” or “blam.” The faster they typed and entered the word, the more food they gained. At a time when simple arcade games were the standard, the Oregon Trail was, as described by the Strong Museum of Play, “a true historical simulation.” The probability of weather conditions and threats changed depending on both season and region. Players successfully hunted 2000-pound bison only to discover that they could only make use of a small portion of its meat before the rest spoiled due to lack of refrigeration. For later versions, Rawitsch consulted the written accounts of pioneers to determine the frequency and type of accidents, conflicts, illnesses, injuries, and obstacles faced. No computer game of such complexity and variability had ever been produced.

The game was a hit with students. Dillenberger recalled that students would both come in early and stay late at school to play the game. Heinemann similarly remembered that students improved in their reading ability because success in the game depended on honing those skills. The Oregon Trail powerfully demonstrated that students were more likely to actively pursue learning if it was presented in the form of a game. Rawitsch later reflected:

“When educators approached computing, they tended to try to create applications that replicated what the teacher used to do: I’m going to quiz you on your math facts. I’m going to show you words and you determine if they’re spelled correctly or not. Oregon Trail, although we didn’t realize it at the time, was really on another level conceptually. And the idea here was to put the player into a story and have the player make decisions and deal with keeping track of things and over time learning a strategy, and in the process learn something about history, geography, resource management, things that would apply to what they were supposed to be learning in the classroom.” (Rignall, 2017).

Archival collections pertaining to the Minnesota Educational Computing Consortium can be found at the Minnesota Historical Society in St. Paul, Minnesota and The Strong: National Museum of Play in Rochester, New York.

Archival collections pertaining to Total Information for Educational Systems can be found at the Charles Babbage Institute in Minneapolis, Minnesota.

Read about the creation of TIES and MECC in an oral history with educator and MECC co-founder Dale LaFrenz, conducted through the Charles Babbage Institute.

Despite the student response, the Oregon Trail game was nearly lost when Rawitsch’s time as a student teacher ended. Then, in 1974, Rawitsch joined the Minnesota Educational Computer Consortium (MECC): an organization chartered by the state legislature to advance computer technology education. The Oregon Trail seemed like a good fit for MECC’s mission, so Rawitsch uploaded an updated version to a computer accessible via teletype by school districts throughout Minnesota. For the next several years the Oregon Trail was “Minnesota’s secret.” That changed in 1978 when MECC partnered with Apple, then a fledgling computer company, to sell educational hardware and software packages to school districts across the country. The initiative was extremely successful and became a seminal moment for both companies. A version of the Oregon Trail sporting basic graphics soon became a fixture in school computer labs nationwide.

65 million copies of various versions of the Oregon Trail have been sold in the years since its creation. It is the most successful educational computer game in history and was inducted into the World Video Game Hall of Fame in 2016. It has enjoyed lasting fame and has become an artifact of nostalgia for a generation of Americans. Perhaps more importantly, the popularity of the Oregon Trail has made it part of the larger story of how computers spread. For many students the game was their first experience using a computer – it demonstrated that the technology was useful not only for business applications but also for fun and leisure. Just as Oregon Trail helped the pioneer experience come alive, it helped the computer itself come alive for the public.

Try your hand at the Oregon Trail

As a covered wagon party of pioneers, you head out west from Independence, Missouri to the Willamette River and valley in Oregon. The Oregon Trail incorporates simulation elements and planning ahead, along with discovery and adventure.

Legacy of the Plains Museum

Located on the Oregon Trail, the Legacy of the Plains Museum features an impressive collection of pioneer and early community artifacts, antique tractors, and farm implements.

Essay by Jonathan Clemens, PhD

Sources and further reading:

The Oregon Trail, MECC, and the Rise of Computer Learning. The Strong Museum. Available Online.

Porges, Seth and Rawitsch, Don. “How ‘the Oregon Trail’ Was Built Without Access to a Computer.” Forbes, November 27, 2017. Available Online.

Rawitsch, Don and Rignall, Jaz. “A Pioneering Game’s Journey: The History of the Oregon Trail.” U.S. Gamer, April 19, 2017. Available Online.

Rossen, Jake. “Sally Died of Dysentery: A History of the Oregon Trail.” Mental Floss, January 11, 2018. Available Online.

Wong, Kevin. “The Forgotten History of ‘The Oregon Trail,’ as Told by Its Creators.” Motherboard, February 15, 2017. Available Online.