The late nineteenth and the early twentieth century saw rapid and influential technological change that justifiably resulted in such names for this period as the electrical age, the automobile age, and the flight age. Largely behind the scenes, this period was also the advent of rapid advances in mechanized data/information processing – the prehistory, if not the early history of, the information age.

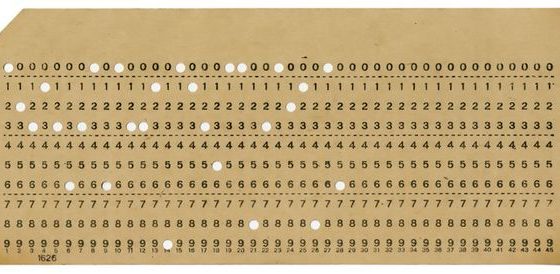

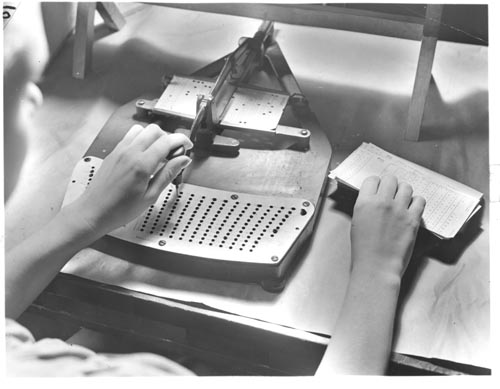

The 1880 U.S. Census, the largest information processing task of its day, had proven that data processing needs far exceeded the capabilities of existing technology as it took around 1500 clerks almost 7 years to process the census information. With plans for the 1890 decennial census to collect substantially more data than the prior one, the U.S. Bureau of the Census held a competition for inventors to create machines to address the needs of this unprecedented information processing challenge. Herman Hollerith, a mining engineer and previous census office worker, won the competition for his electromechanical punch card tabulation machine. The system consisted of using card punches and tabulation machines, where holes in cards facilitated the completion of circuits by spring loaded steel pins on the tabulators, to read and process punched information.

Archival collections pertaining to Herman Hollerith, Hollerith machines, the Tabulating Machine Company, and more can be found at the Library of Congress in Washington, D.C.

Visit the Computer History Museum’s online exhibit to learn more about the role of punched cards in computing.

Hollerith incorporated the Tabulating Machine Company (TMC) in 1896 and went on to provide tabulation machines for the 1900 U.S. Census, many overseas censuses (Great Britain, Germany, France, Austria, Russia, Norway, and Italy), and to meet the information processing needs of companies in a number of fields, including the railroad, steel, and insurance industries. In 1911 businessman Charles Flint orchestrated the combination of TMC and three other firms selling various types of business machinery – from time-clocks to meat scales – to create the Computing-Tabulating-Recording Company (C-T-R).

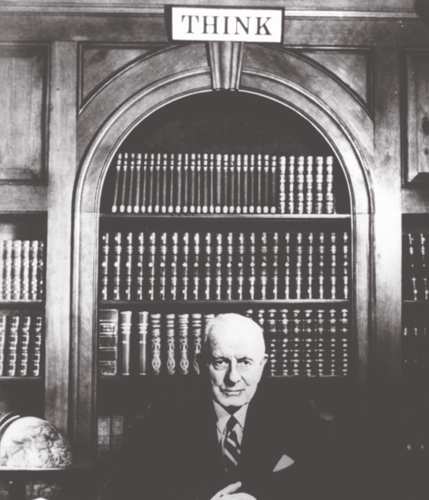

Hollerith initially consulted with C-T-R, but retired shortly after this combination. In 1914 C-T-R hired National Cash Register (NCR) sales manager Thomas J. Watson to lead the company. Watson brought many of the famed sales management practices of NCR – including sales territories, quotas, sales education, strict dress codes, and performance-based reward structures – to C-T-R , along with the famed “THINK” motto/sign Watson had developed at NCR. Punched card tabulation technology grew rapidly (far faster than the other businesses) and C-T-R quickly secured the majority of the national and international market for punched card tabulation machines. Despite C-T-R’s growth, there were nonetheless larger players in overall office machine market including Remington Rand, Burroughs, and NCR – companies specializing in typewriters, cash registers, and filing systems and accounting machines.

In 1924, with a large presence around the world, C-T-R changed its name to International Business Machines, the name previously used by its Canadian subsidiary. In 1928 IBM introduced an 80 column card with rectangular holes, which became a dominant standard (something user organizations desperately wanted, because switching systems was expensive), and helped solidify the company’s success in the data processing market and added mightily to IBM’s top and bottom lines – through the early 1950s the standard cards were still 20 percent of the firm’s annual revenue and 30 percent of profits. The printed statement on IBM cards “do not fold, spindle, or mutilate,” became iconic.

In 1932 IBM launched Service Bureau Division (SBD), which allowed customers to outsource their data processing to IBM processing bureaus. While most large companies and organizations (including government) leased IBM equipment and maintained internal data processing departments or “tabulation rooms,” the SBD alternative was especially important for smaller enterprises where purchases or leases of tabulation machines were prohibitively expensive. From the start of C-T-R the company had bundled – provided without additional charge – hardware sales/leases with set-up, maintenance and advisory services but with SBD, IBM began to monetize data processing services. Part of the rationale with launching SBD (which was always generating less than 4 percent of IBM’s overall revenue) was to try and recruit businesses regardless of their size and to get them tied into IBM systems. Many of the SBD users, as they grew, graduated to acquiring IBM equipment to use in-house.

From the start of Great Depression and continuing through its toughest years in the early to middle 1930s, Watson famously expanded operations and employment while its primary punch card tabulator competitor Remington Rand (a diversified and sizable office machine supplier, but one with only roughly 15 percent of the punch card tabulation machine market, compared to IBM’s approximately 80 percent) retrenched and laid off staff. Watson was prescient to foresee the expanding information processing needs of the federal government with President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal and the Social Security Act of 1935. The Social Security Administration greatly expanded the federal government’s requirements for data processing and IBM, as the leading punch card tabulation machine supplier to the federal government, strongly capitalized on these needs. The government business helped subsidize efforts to further build its base of customers in the private sector during lean economic times. Continuing its momentum during the latter years of the depression and throughout World War II, IBM emerged the largest office machine firm in the world in revenue by the end of the war, and its double digit profit margin in the mid-1940s was between two and four times larger than all of its major office machine peers (Remington Rand, Burroughs, NCR, and Underwood).

IBM’s strong financial position prior to, during, and after World War II placed it in a highly favorable position to invest aggressively in scientific computation as well as electronics research in the 1930s and 1940s. IBM had partnered with Columbia University since 1930 on scientific computation, which was solidified and extended with the 1937 establishment of the joint Columbia University and IBM Thomas J. Watson Astronomical Computing Bureau. The Bureau was run by IBM engineer Wallace Eckert, an instrumental figure in design of what would become the leading scientific computation machine of its day, the IBM Selective Sequence Electronic Calculator, dedicated in January 1948.

Although Thomas Watson, Sr., remained the official leader of IBM until months before his death in 1956, his son had assumed much of the day-to-day management of the firm since 1952. Thomas J. Watson, Jr., coupled with senior advisors James Birkenstock and Cuthbert Hurd, led IBM to enter and soon lead in the digital computer field. The firm’s first computers were the Defense Calculator, or IBM 701, delivered in 1953, and the more economical and far more lucrative IBM 650, in 1954.

Even as IBM steadily and successfully transitioned its organizational customers from punched card tabulation machinery to computing machines, punch card tabulation equipment remained a larger source of revenue for the firm until 1963. And it was thanks, in part, to this technology that IBM became dominant in mainframe computers: punched card tabulation machines allowed IBM to develop a global customer base, the capital from sales and leases of the machines provided IBM with financial and technical resources to develop new technologies, and IBM’s skilled sales force helped sell new and old customers alike on novel computing technologies at mid-century.

Listen to an oral history through the Charles Babbage Institute with Thomas Watson, Jr., (IBM Chairman from 1952-1971) and James Birkenstock (IBM Corporate Vice President from 1958-1966). Here they discuss the relationship between IBM and the British Tabulating Machine Company, an important UK-based computing company.

Explore more about the history of IBM and their machines via the company’s online collections.

Essay by Jeffrey R. Yost, Historian and Director of Charles Babbage Institute

Sources:

Martin Campbell-Kelly, William Aspray, Nathan Ensmenger, and Jeffrey R. Yost. Computer: A History of the Information Machine, 3rd. Edition. (Westview, 2014).

Jeffrey R. Yost, ed. The IBM Century: Creating the IT Revolution (IEEE Computer Society, 2011).

Jeffrey R. Yost. Making IT Work: A History of the Computer Services Industry (MIT Press, 2017).