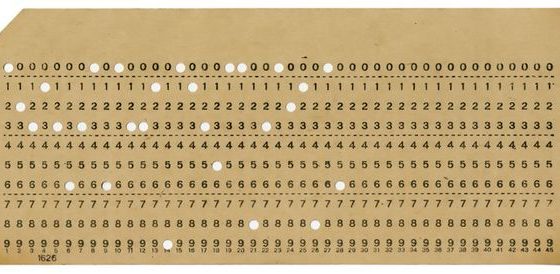

IBM, a company founded as C-T-R in 1911 and renamed International Business Machines in 1924, built upon its long established success in punch card tabulation machines, to creatively destroy this technology by entering the computer business in the early 1950s. In essence, IBM steadily cannibalized the existing data processing technology it had led in for decades for a far more lucrative one – digital computers. IBM was thus a critical contributor to the launch and advancement of the information/digital age in the mid-twentieth century.

IBM purposefully chose to take a measured approach to entering the digital computer market. IBM’s lucrative base of tabulation machine customers, and thoughtful executive leadership and planning, meant they did not have to make the first move. Instead, two startup companies launched the computer industry in 1946: Eckert-Mauchly Computer Corporation of Philadelphia (spawned by the two founders, J. Presper Eckert and John Mauchly, who had led the Electronic Numerical Integrator and Computer project, or ENIAC), and Engineering Research Associates (ERA) in St. Paul, Minnesota. Both were acquired by office machine firm Remington Rand, in 1950 and 1952 respectively. As a result of the 1950 Eckert-Mauchly acquisition, Remington Rand was the first company to come to market with a major computer. The Universal Automatic Computer, or UNIVAC, launch in 1951, more than a year ahead of IBM’s first digital computer offering. Though the name UNIVAC became synonymous with computer for a time , fewer than 50 of these million dollar mainframes were installed; nonetheless it was a meaningful – if modest – financial success for first-mover Remington Rand.

UNIVAC’s designer, J. Presper Eckert, operator Harold Sweeney, and journalist Walter Cronkite sit in front of the UNIVAC that would go on to successfully predict Dwight D. Eisenhower’s landslide victory in the 1952 Presidential election on CBS News. UNIVAC gained widespread public attention after this event. The computer’s prediction was based on an algorithm developed by Grace Hopper and her programming team at Remington Rand.

Courtesy of Computer History Museum

Despite some important installations of the UNIVAC system, in a technical sense IBM never really fell behind in computing. It had been investing heavily in electronics research and development since the 1940s, and leadership began examining proper strategic entry points into this market at the start of the 1950s. Thomas Watson Jr. and IBM executives quickly recognized that the transition would be more rapid in the specialized aerospace/big science/defense market, and steady but more gradual in the larger business data process market. Companies would eventually have to transition from their largely successful tabulation rooms and staff trained in this field, to the entirely new, different, and far more expensive field of digital computers. As such, IBM’s transition from primarily a punched card tabulation machine company to primarily a computer company took place over the better part of a decade and began with its first digital electronic computer, the Defense Calculator. This defense and science oriented machine, also referred to as the IBM 701, was announced in 1952 and deliveries began the following year. Less than 20 were produced, mainly based on pre-orders for aerospace firms and government—including installations at the National Security Agency, Boeing, Lockheed Aircraft, Douglas Aircraft, the U.S. Weather Bureau, and General Motors.

IBM followed up this computer with a commercial-focused and more aggressively priced IBM 650 in 1954. The IBM 650 could rent for roughly $1,000/month in common configurations. This system was called the Model T of computers, being the first digital computer that truly was mass produced (most other computers of the time had sold in the dozens overall, not the thousands). And while IBM 650 was the transition computer for many businesses to enter the computer age in the second half of the 1950s, it also was utilized as an important scientific computer by a number of university computer centers and laboratories based on its relative affordability.

Concomitant to the IBM 650 and seeking a mass organizational market, IBM also targeted supplying (in low volume) the highest end, massive computers for the federal government. In the mid-1950s IBM received a contract for more than four dozen AN/FSQ-7 Semi-Automatic Ground Environment control/monitoring computers. These computers, which were part of a radar and air defense U.S. Air Force system, were by far the largest computers ever built: each “Q-7,” housed in duplex for safe redundancy at SAGE sites, took up half an acre of floor space, weighed 250 tons, contained 55,000 vacuum tubes, and could execute 75,000 instructions per second. This was an unprecedented project in size and technology that introduced IBM to real-time computing and networking, areas which completely changed possibilities for computers and proved useful down the line for IBM with future projects for both government and commercial clients. Although project was at times unweildy, It also yielded revenue of $500 million for IBM.

Finally, at the end of the 1950s IBM announced their 1401 computer. This machine was transistorized rather than tube based, and including sales and leases eventually achieved over 10,000 installations. With these machines, IBM became the leading company for supplying computers for business data processing, as well as for government and scientific computing. The company had more than 60 percent market share in the overall computing field by the end of the 1950s.

Even with its market dominance, IBM had a longer term problem. At the start of the 1960s the company had a number of individually successful, but disparate and non-compatible lines of computers. This was not good for customers and it was expensive for the company to maintain services. To address this IBM formed the SPREAD Task Group which came up with a plan for a compatible line of family computers with different processing capabilities and price-points to be delivered in 1964 and named for the full circle of capabilities it provided: the IBM System/360 Series. This included less expensive and less powerful models, 20 and 30, to the model 90 that possessed near “supercomputer” capabilities.

System/360 represented both a major opportunity and risk that one prominent journalist referred to as “IBM’s $5 billion gamble,” maintaining that IBM was betting the company. While a bit of an exaggeration, as IBM likely would have survived regardless of the outcome of the new family, System/360 was critical to IBM and ultimately was a major success, though it was not without its challenges along the way. The greatest challenge was the operating system, or OS/360. Large software systems are difficult to produce and despite efforts to the contrary software production is largely a craft enterprise that is not conducive to factory type production to scale up. Something OS/360 project leader Frederick Brooks later conveyed in a classic text on software engineering, The Mythical Man Month, is that adding “man-months” late in a project can further delay and complicate a major software project rather than accelerate its completion.

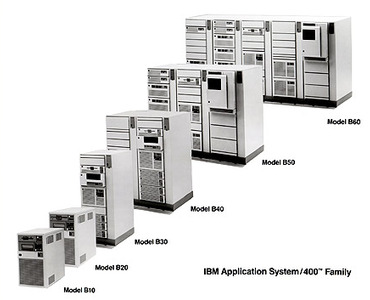

Highly successful for years after its release in 1964, the System/360 line added greatly to IBM’s top and bottom lines and helped IBM achieve well over 70 percent market share both domestically and worldwide. Though most known for its iconic mainframes such as the System/360 line and the follow-on 1970s IBM System/370 line, IBM also produced a midrange family of computers at a facility added in the middle 1950s in Rochester, Minnesota. IBM had sales and facilities worldwide, but major plants for research and manufacturing were limited to cities/towns in New York such as Endicott, the original headquarters of C-T-R, Armonk, Poughkeepsie, and Kingston, and one west coast facility in San Jose, California (which along with Hewlett-Packard, Fairchild Semiconductor, and successor semiconductor firms like Intel, would be critical to defining/shaping Silicon Valley). IBM chose Rochester, Minnesota – initially just to manufacturer existing products, but soon it became a research facility spawning new ones – because of its educated workforce (with the University of Minnesota-Minneapolis an hour’s drive away and the famed Mayo Clinic in Rochester), relative lack of union activity, and moderate wages in the area. The first midrange IBM computer was the System 3 in 1969, followed by Systems 32, 34, 38, 36, in the 1970s and early 1980s, and the high influential AS/400 in the late 1980s .

In 1990 IBM Rochester won the prestigious Malcolm Baldrige Quality Award for the AS/400, a national award recognizing quality production and competitiveness. By the early 1990s AS/400 had produced more than $14 billion in annual revenue for IBM, more than the entire revenue of minicomputing giant Digital Equipment Corporation.

Read an oral history via the Charles Babbage Institute with computer programmer David Schleicher who worked on various projects at IBM’s Rochester facilities, including Fort Knox, System/38, and AS/400.

In addition to mainframes and midrange computers, IBM was also a major contributor in software and services, though prior to 1970 most software and services were bundled into the price of hardware, and even after its 1969 unbundling announcement (for software and services), the implementation of separately pricing software and services from hardware in the 1970s was only partial. From shortly after IBM’s first digital computers, it produced software tools (such as compilers and programming languages), software products (including multiple important offerings in the database field), and services. Under the project leadership of John Backus, an IBM team in the late 1950s developed the highly influential scientific programming language Formula Translator, or FORTRAN. In terms of database and communications software products, IBM created Generalized Information System and the Customer Information System in the late 1960s – tools highly valuable to managing data and for transaction processing. In the services area (and fully bundled into the several mainframes and more than 1,500 modified IBM Selectric typewriters with CRT screen terminals it sold), IBM pioneered the first real-time, networked airline seat reservation system. Developed for American Airlines, SABRE was a $30 million project that began in the late 1950s and was fully operational by the middle 1960s. IBM also provided services for the government out of its Federal Systems Division, which included mission control IT infrastructure and support for NASA in Houston, and was critical to putting a man on the moon.

The SABRE project, as with many Federal Systems projects including work for NASA, took advantage of a new class of engineers that IBM launched in 1960s, Systems Engineers, who specialized in programming and integrating large-scale systems for advanced (often real-time, networked) applications. Systems Engineers, which included five levels and elevated the prestige of high-level work on-site for customers to correspond with internally focused IBM computer design engineers, was an IBM employment category that built on the legacy of the mid-1930s Systems Services Women’s Corp of college educated and advanced trained women employees providing advanced services to customers on applications, first in punched card tabulation, and by the mid-1950s (by then numbering more than 500 women) in programming and computing.

IBM’s executives, in making the unbundling decision at the end of the 1960s, were influenced by their anticipation of a Department of Justice antitrust lawsuit that was filed shortly after the announcement of unbundling by IBM in 1969. An IT services industry that had begun in the early to middle 1950s with computer consulting, and shortly thereafter programming services and outsourced data processing, and a software products industry that got going in the first half of the 1960s, arguably were greatly hindered by a dominant mainframe supplier giving away software and services. But even if IBM’s unbundling had been complete in the 1970s (which it was not), there were many other practices that might cause unfair advantages across business areas. As part of a Control Data Corporation 1967 lawsuit for anti-competitive practices, IBM settled in 1973 by selling (on very favorable terms) to Control Data IBM’s Service Bureau Corporation (its wholly owned subsidiary for outsourced data processing and computer time-sharing, a spinoff of Service Bureau Division that shifted to being computer based in the second half of the 1950s ). The DOJ lawsuit lasted a dozen years, and the DOJ presented a great amount of damaging evidence against, but ultimately the case was dismissed in 1981 in the face of the far less aggressive antitrust policy of newly elected President Ronald Reagan. Not only was the new administration less keen on prosecuting an legendary American computer company for antitrust violations, IBM did not have the real or perceived dominance in computing in 1981 that it did in the late 1960s. The growth of the minicomputer market and its leader, Digital Equipment Corporation, lent some balance to the field. And the advent of personal computers meant IBM likely would have a much smaller portion of computer market share in the 1980s and 1990s than in the 1960s and 1970s.

Archival materials pertaining to the U.S. Department of Justice’s thirteen-year lawsuit against IBM (1969-1982) for antitrust violations can be found in the Martin Goetz papers at the Charles Babbage Institute, University of Minnesota.

Listen to an oral history interview via the Charles Babbage Institute with Elmer Trousdale, a lawyer that worked with Control Data Corporation when they filed suit against IBM in 1967 for anti-competitive practices.

Visit the Computer History Museum’s research facilities in Fremont, California to explore the archival collection of Digital Equipment Corporation, IBM’s minicomputer competitor.

IBM broke with practice of internal development of products and components by quickly outsourcing much of the development of the IBM PC in 1981. It was more than a half decade after the launch of personal computing kits such as the Altair 8800, and three years after the far more user friendly Apple II (out in 1977), and some successful models from Commodore and others. Though IBM briefly became an industry leader in PCs, its operating system/platform was not protected and clone manufacturers Compaq and Dell, along with the primary suppliers of PC operating systems and office application software, and microprocessors, Microsoft and Intel (sometimes referred to as Wintel, Windows and Intel), were the major beneficiaries of the rapid growth of PC’s. With this, IBM faced major struggles by the late 1980s and a fundamental restructuring of its profit centers in the early 1990s led it on the path to become primarily a software and services company, with the latter being its primary business today. In the services space, IBM is focused on consulting, and particularly on the faster growth areas of big data analytics with its Watson artificial intelligence systems (which received a public relations boost by winning game show Jeopardy against top human players in 2011), and cloud services.

Essay by Jeffrey R. Yost, Historian and Director of Charles Babbage Institute

Sources:

Frederick Brooks. The Mythical Man-Month: Essays on Software Engineering (Addison-Wesley, 1975).

Martin Campbell-Kelly, William Aspray, Nathan Ensmenger, and Jeffrey R. Yost. Computer: A History of the Information Machine, 3rd. Edition. (Westview, 2014).

Emerson W. Pugh. Building IBM: Shaping an Industry and Its Technology (MIT, 1995).

Jeffrey R. Yost, ed. The IBM Century: Creating the IT Revolution (IEEE Computer Society, 2011).

Jeffrey R. Yost. Making IT Work: A History of the Computer Services Industry (MIT Press, 2017).