In 1991 a team of programmers at the University of Minnesota created the first popular means of using the internet. They called it “Gopher:” a nod to both the slang “go-fer,” meaning to fetch something, and the Golden Gopher mascot. Gopher’s client-server protocol allowed users to explore and view online content: a “web browser” before the “web.” It became the software of the internet when the medium was still in its infancy as a public information resource. Gopher dominated for a few crucial years before the World Wide Web, and during that time it helped define what the internet was and what it was for.

Project lead Mark McCahill and primary software designer Farhad Anklesaria built Gopher as a solution to a problem at the University of Minnesota. In 1990 University officials proposed a mainframe Campus Wide Information System: a way for faculty, staff, and students to access university information and send e-mail. The project quickly became bogged down by bureaucracy and was plagued by factionalism. Anklesaria later remembered it as “a classic design-by-committee monstrosity.” To get around these issues, McCahill, Anklesaria, and a small team of programmers wrote the code for Gopher without official approval and using readily available personal computers rather than a University mainframe.

Read an oral history interview with Mark McCahill, conducted at the Charles Babbage Institute.

Learn more about other computing projects developed at academic institutions across the United States through the Academic Computing Collection housed at the Charles Babbage Institute.

The software worked beautifully but was initially rejected by a University of Minnesota committee because it didn’t suit their vision for the project. In response, the Gopher team released the program for free using File-Transfer Protocol: the most popular way to share software at the time. The strategy worked. Programmer Robert Alberti later recalled:

“[Gopher] was the first viral software. All these people started calling the [University of Minnesota] and pestering the president and other administrators, saying, ‘This Gopher thing is great, when are you going to release a new version?’ And the administrators said, ‘What are you talking about?”

Shortly thereafter, the University gave in to popular demand and Gopher was officially approved for distribution.

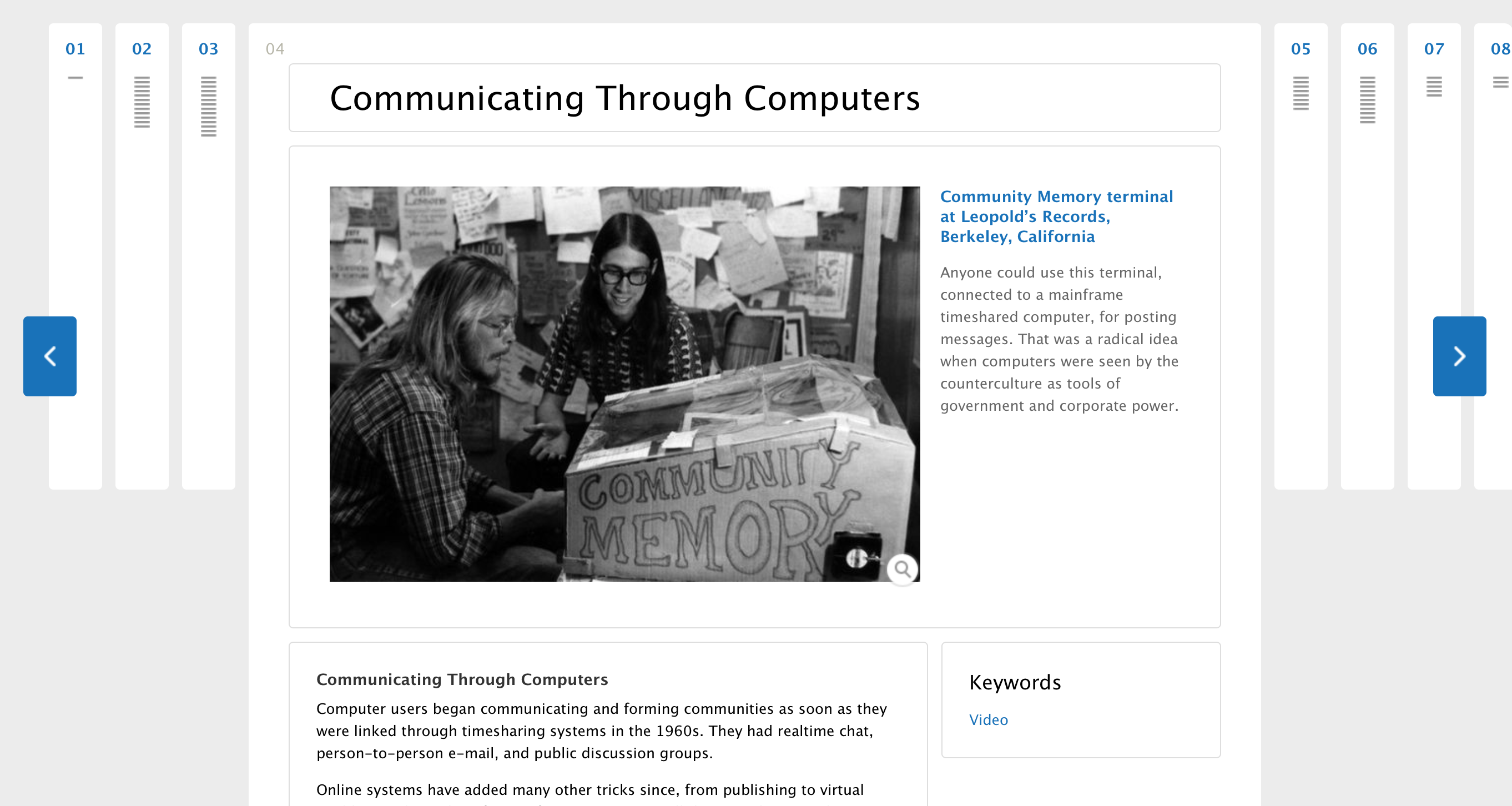

Gopher was crucial to the popularization of the internet. When it was introduced the medium was primarily seen as an esoteric tool for institutions and hobbyists. Gopher changed that by making online content more approachable and accessible. McCahill explained:

“People were looking to expand the internet beyond physicist’s stuff. Gopher could do that. It was simple to use, it could network lots and lots of computers. It gave people a reason to say, hey, this internet is good.”

Gopher struck a chord and quickly spread to hundreds of servers across the country. As described by an article in 1994:

“Millions of Internet citizens use Gopher to burrow into electronic libraries on every continent to find documents, pictures, animations, sounds, and video clips” (Deyo).

Annual Gopher conferences were attended by representatives from companies like Apple, IBM, Microsoft, and the World Bank. At the peak of its popularity there were 6,958 Gopher servers in operation: two and half times its closest competitor. When Tim Berners-Lee released the World Wide Web to the public, it spread through file sharing on Gopher.

Gopher remained the most popular means of accessing the internet until 1994 but waned thereafter. Two major factors contributed to its decline. First, in 1993 the University of Minnesota announced that it would charge licensing fees for commercial Gopher users. The news was met with a severe backlash from the user community. Many felt the move was a betrayal of the ethics of the internet, and it caused Gopher to lose both social capital and credibility. According to Alberti, licensing “socially killed gopher.” Second, changes to internet hardware gradually made Gopher less appealing. As put by McCahill, Gopher was designed within “the limits of what the technology (at the time) could do.” It was deliberately text rich because images were slow to load on the comparatively slow modems of the early 1990s. The decision to prioritize text made Gopher relatively fast while the more image-oriented World Wide Web languished in slow speeds (the “World Wide Wait”). However, by 1994 improvements in modem technology had turned this asset into a liability. Increased speeds made it easier to display pictures, and images gradually became important to both online commerce and aesthetics. The World Wide Web began to take over as the platform for the commercial internet, and by the end of 1994 Gopher was practically obsolete. Though it continued to operate, it would never again be the dominant means of getting online.

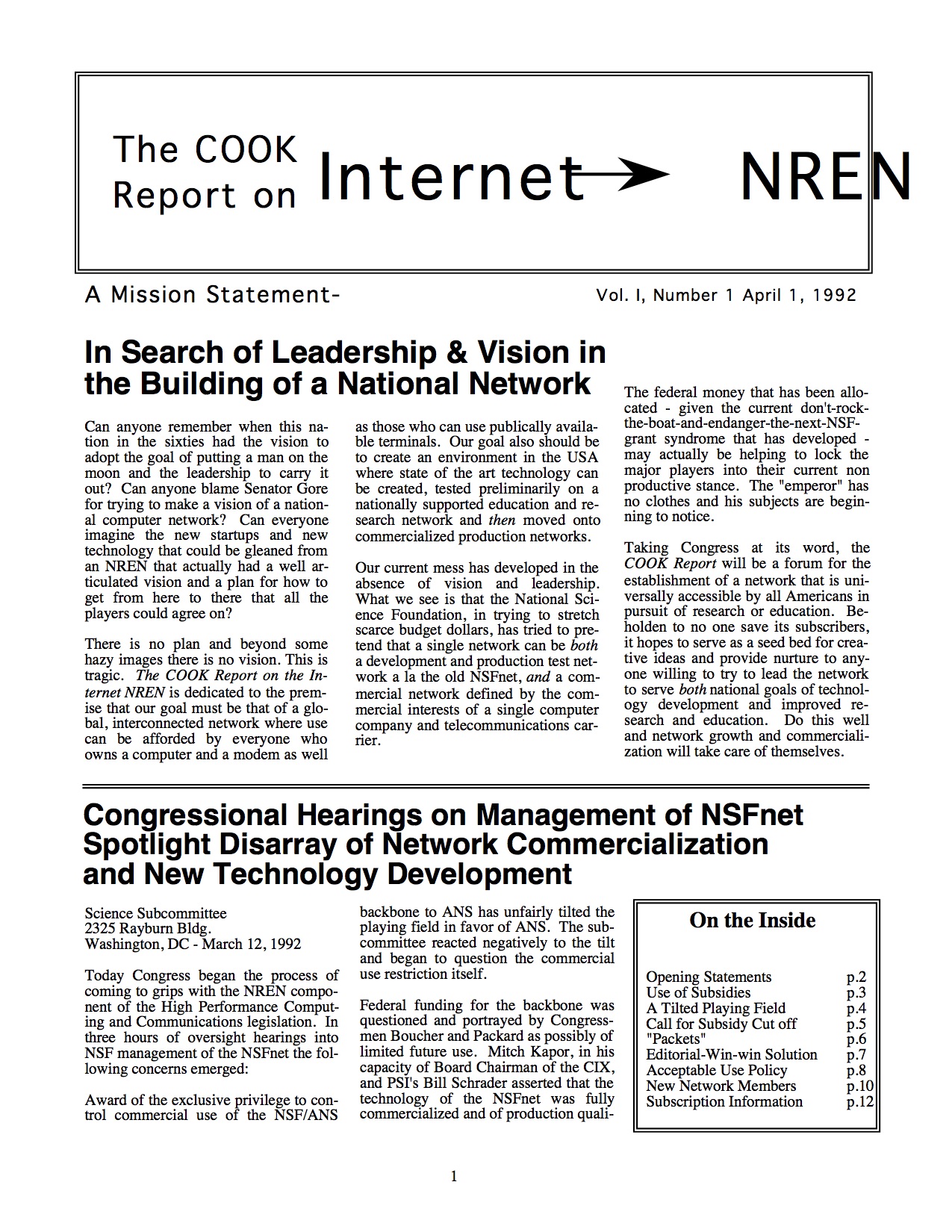

Explore the Charles Babbage Institute’s digitized collection of The COOK Report on Internet Protocol.

Even though its prominence was short lived, Gopher defined expectations for how the internet functioned in important ways. It introduced the idea of saving internet resources as “bookmarks.” It was the first popular software to include hyperlinks connecting to other sites: helping to define what a “link” was and how it functioned. It featured one of the first search engines. Perhaps most importantly, Gopher helped transform the internet from something technical and academic to something accessible. As described by Thomas J. Misa:

“Gopher was the first internet application to gain global use as a means for interactively sharing content” (Misa). It popularized the internet as a public medium, and it helped set the stage for the modern internet.

Want to learn more about the Internet?

Visit to the Computer History Museum’s online exhibit “The Web” to learn more about the history of the internet.

Essay by Jonathan Clemens, PhD

Deyo, Steve. “Gopher Goes Global: the Information Superhighway Starts Here.” Minnesota, Vol. 93, No. 5, May-June 1994, p. 48-49.

Frana, Philip. “Before the Web There Was Gopher,” IEEE Annals of the History of Computing, Vol. 26, No. 1, 2004, p. 20-41.

Gihring, Tim. “The Rise and Fall of Gopher Protocol.” MinnPost, August 11, 2016. Access Resource Online.

McCahill, Mark. Interview with Philip L. Frana. Minneapolis, MN, September 13, 2001. The Charles Babbage Institute. Access Resource Online.

Misa, Thomas J. Digital State: The Story of Minnesota’s Computing Industry. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013, P. 215-217.